Karma is Not Justice, and more

10 Corrections to common American misconceptions of Buddhism

This piece is inspired by many conversations with friends and family over the past two years since my deep dive into Dharma. I try to stay broad, but it will inevitably lean towards representing the sects of Buddhism I have the most exposure to: Theravada and Vajrayana. I really don’t know anything about Zen.

Quicklinks

1. Buddhism is a Religion, and it is not Atheistic

3. Most Buddhists are not vegetarian.

4. Reincarnation/Rebirth is subtler than you think it is.

6. Emptiness is not Nihilistic or uncaring, and it does not mean that nothing matters.

7. Faith is still important in Buddhism — it is just measured.

8. Buddhism does not claim to be the only true religion or path, but it also doesn’t think everybody is right.

9. Enlightenment is a process, not a state.

10. Enlightenment is not Infallibility.

Dive into Dharma

I was interested in Buddhism in the abstract long before I truly started practicing it. I had an Aunt and a couple other influences who were into it growing up, and I remember first reading a graphic-novel style intro to the teachings of the Buddha when I was…10? 12? And like most Americans, I had a very cartoon-style idea of Buddhism. Something like “The Buddha discovered that by renouncing all the things you want and meditating a lot, you could be perfectly happy all the time.” Inspiring and fascinating, but definitely a caricature of the truth.

By age 33, I had a somewhat deeper, but still woefully inadequate understanding. I gave a talk on some Westernized Buddhist Psychology at a sort of hippy conference (talk below if you’re interested). I thought it was a pretty good talk, and people said they liked it, but what really changed my life came next. An older lady from the community, who radiates a powerful presence came up to me. She expressed that she loved the talk and related it to her own spiritual experience. I quickly clarified that what I was doing was mostly philosophy. I did Taichi, but I didn’t really have a sitting meditation practice. She stared at me and said “You need to go on a 14-day meditation retreat. Things will happen fast for you.” She made a motion like a lightning striking a tree with her hand. “I have a sense of these things.” When mystical older ladies tell you how to run your life, you should consider it very seriously.

So, I dove in. I started meditating every day, and I signed up for a retreat. The rest of the story is for a different essay, but in short, it has been life-changing. In the last two years I’ve spent a lot of time meditating, talking to teachers, and reading everything from new popular Western Buddhist science books to Sutras older than the Bible. Relative to most of the other Buddhists I interact with, I’m new to it all, and very much a student. However, I learn best by teaching, so I’ve also spent lots of time talking about Buddhism, spirituality, and meditation to friends, family, and community members who aren’t so steeped in this world.

Dr. Tucker Peck, Psychotherapist and Dharma teacher also notes the importance of integrating one’s experience with their non-spiritual friends.

In doing so, I’ve realized that my past self, and most Americans (even highly-educated bay area hippies), have many massive misconceptions about Buddhism! There are probably many causes for this. Some are due to the neo-Platonic Judeo-Christian Scientific thought that is simply in the water supply here. Some are due to the way Buddhism was first introduced to the West. Some is due to attempts by secular thinkers to demythologize Buddhism, and extract the “useful parts” without the dogma.

Regardless of the reasons, and because I’m working hard and don’t have as much time to write these days, I thought I’d compose a Buzzfeed-style List of Corrections to the top 10 common American misconceptions about Buddhism!

1. Buddhism is a Religion, and it is not Atheistic.

“…It’s really more of a philosophy…”

- Every secular Westerner who thinks the idea of Buddhism is cool

If I had a dollar for every time I heard the above sentiment…1 Yes, the idea of Buddhism is cool, and yes there is lots of philosophy (both Eastern and Western) that has been influenced by Buddhism, but Buddhism is definitely a religion2. Like most major religions, it has a founder who was (at least) a powerful mystic. It has holy books and ideas of what is sacred. It has a worldview, practices, and shared ceremonies and ritual. It has ideas of how one should behave. And importantly, it is very much inclusive of (and, in one sense, entirely about) a connection with the divine. It just talks about the divine pretty differently from the way that Abrahamic religions do.

Similarly, the idea that Buddhism is an “Atheistic religion” is simply not true: Brahma, the same creator deity shared by Hinduism, appears many times in the Pali Cannon (the closest thing we have to a primary source of the original lectures of the Buddha). He features along with many other devas, gandharvas, and asuras.

However, I will admit there is something unusual in the way Buddhism discusses deities: Lord Brahma is kind of a side character. The main character of the Pali Cannon is the Buddha, and the main content is the path of liberation. In stark contrast to Abrahamic religions (except perhaps Baha’i and Sufism), the Buddhist mainstream is mystic3: it is much more concerned with method and direct experience than it is with conceptual belief. In the Buddha’s words:

“I teach only suffering and the end of suffering.”

- The Buddha, MN 22, SN 22.86

In addition, Buddhists are not likely to list anything about the divine in their definition of a Buddhist. A Thai Buddhist told me that the usual Thai definition is if you believe the Buddha was Enlightened, that Enlightenment means something, and you try to follow his teachings, you are a Buddhist.4

Things get a lot more confusing if you try to ask if Buddhism is monotheistic, polytheistic, or something else:

“In Tibet, they worship hundreds of Gods and find none. In India they worship one, and find hundreds.”

- Old saying

We run into questions like…is a god a being? Well, a core tenant of Buddhism is that individuated, independent, immortal beings don’t exist, including you.

“Is Avolokiteshvara [a Buddhist deity] real? He’s as real as you are.”

-Michael Taft, Dharma teacher of some note

Buddhism teaches from multiple “views” simultaneously — which we might, in common English, call “frames” or “perspectives”. It is considered important to understand the view from which one is currently speaking. To be able to speak at all, we need to deal in concepts, even while acknowledging that concepts are, from “The Absolute View”, illusion. The question of whether or not God or gods exist depends on the view. But I don’t think Buddhism advocates any view where you exist and God does not! (the default American Atheist position)

I play with these ideas of Being much more in another piece:

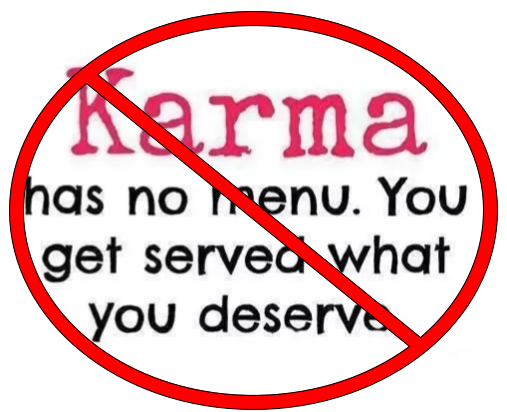

2. Karma is not Justice.

This misconception is clearly cultural, and it is so widespread that I made it the title of this essay. Judeo-Christianity, and by extension, Western culture, deeply believes in an individual’s agency to make their will manifest on the world. Christian Theologists and Western philosophers alike grapple with questions of Free Will, Blame, Culpability, and Punishment. Steeped in this cultural background of individual agency, it is natural to think that Karma is some kind of cosmic justice: “Good things that happen are rewards for good actions I have taken, and bad things are punishments for wrong actions.” Even the Western religion that took predestination to an extreme, Calvinism, still emphasized that salvation or damnation was the result of your individual actions.

This idea of Karma is almost entirely incorrect. Karma means “action”, yes, and the concept includes the way that bad action begets bad results, and good action begets good results. But it doesn’t always mean your action. (reminder, Buddhists don’t believe in the individual self) Sometimes you reap what other people sow. Is this Just? Not really — it’s pretty orthogonal to Justice5. So if Karma (or kamma) is about the results of actions, does it just mean “there are causes and effects”? That sounds so trivial as to be meaningless. What is the idea of Karma actually getting at?

The closest Western idiom I can think of that captures the correct sense is “Hurt people, hurt people”. Karma is very broad, but one of the most common types of bad karma is Generational Trauma. Is generational trauma your fault? Do you deserve it? The Western caricature of Karma would suggest that you do.

Of course, any sane person, and any Buddhist, will tell you that your trauma is not your fault! But it can be your karma. Someone in the past took bad actions, and you are now suffering as a result. You have the opportunity to either clean it up, or pass it on to someone else. (which may well be you again) A better translation than “justice” might be “conditioning”, referring both to internal psychological conditioning as well as the conditions of circumstances.

Karma is a much less individualistic and paternalistic notion than Americans imagine it to be. Instead, it is the naturally-arising virtuous and vicious cycles that self-perpetuate via causation and conditioning, both inside and out. It is the awareness that we are all mirrors, we are all one, and when you hurt or help someone, that action echoes forwards and backwards through time. Don’t pay it back, pay it forwards.

3. Most Buddhists are not vegetarian.

This one is a minor misconception, but widespread. Americans seem to have the odd idea that all Buddhism mandates vegetarianism. This is simply not the case, and it’s not a matter of how adherent you are (which, as in any religion, varies). There are of course, many sects of Buddhism, and some of them do encourage6 vegetarianism, but they are in the minority.

If you go by the numbers, you find that even in India, in which cultural vegetarianism is widespread, Buddhists are less vegetarian than Hindus, Jains, or Sikhs. Worldwide, around 25% of Buddhists are vegetarian, mostly Chinese Mahayana.7 Even the Dalai Lama is not strictly vegetarian.

If you go “by the book” of fundamentalist Theravada Buddhism, you find that laypeople are not at all expected to abstain from meat. Monks are expected to not butcher animals (along with hundreds of other rules), but they are permitted to eat meat that was butchered by someone else so long as it was not intended for them specifically at the point of killing. (The consequentialists will hate that one!) The last Theravada retreat I went to served meat to participants, though vegetarian options were available.

If you go by the spirit, killing an animal does generate bad karma, however much less so if it is not done out of hatred. The Buddhist precept against killing8 is, as I have seen it explained and practiced, about killing out of the desire to harm. Just as it is ok to kill to protect your family, it is ok to kill to sustain yourself as a natural omnivore. Both of these choices will have karmic ramifications regardless, but what kind will depend on the circumstances. Perfection is just another vice. When eating animals, do so with gratitude for the nourishment and awareness of the life of the animal. Becoming vegetarian could be the right choice for you, but it will depend on lots of factors.

There is also the idea that many people, as they advance in their practice, are likely to become more vegetarian, and in general prefer lighter foods. This is more of an outcome than a mandate, and in some cases meat is even recommended to treat different energetic situations.

4. Reincarnation/Rebirth is subtler than you think it is.

If I mention that I’m Buddhist, this is one of the first things to pop up. Something like “I always liked the idea of reincarnation”, or “what do you think you were in your past lives?”. The American/Christian idea of reincarnation tends to be something like “After you die, instead of going to heaven, your soul becomes some new animal or being, and then you’ll experience life that way, on and on forever”. Well…it’s a bit more subtle than that, and this is another one that varies widely by sect and the surrounding culture. But before moving on, let’s remember two super foundational Buddhist notions, two of the Three Marks of Existence9:

anicca - Impermanence. Nothing lasts forever. No person, no being, no soul.

anatta - Non-self. There is no individual soul. Even though we often feel that way, relieving ourselves of this delusion is pretty much the point of (vipassana) meditation.

The Diamond Sutra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra), another of the most important Buddhist texts (and first dated printed book in human history), really hammers this point over and over:

Subhuti, no one can be called a bodhisattva (enlightened person) who creates the perception of a self, or who creates the perception of a being, a life, or a soul.

How do we reconcile the illusory nature of self with all the talk of karmic perpetuation and rebirth?

It should be noted, incidentally, that Buddhists prefer to speak, not of reincarnation, but of rebirth. Reincarnation is the doctrine that there is a transmigrating soul or spirit that passes on from life to life…In MN 38, the monk Sāti was severely rebuked for declaring that “this very consciousness” transmigrates, whereas in reality a new consciousness arises at rebirth dependent on the old. Nevertheless, there is an illusion of continuity in much the same way as there is within this life.

- Marice Walshe, translation of the Dīgha Nikāya.

Completely understanding the sense in which Buddhists mean you don’t exist might involve a lot of thinking about Star Trek transporters. Noticing it in your own experience might be equivalent to Enlightenment, so I won’t attempt to complete that discussion here. For now, don’t worry if anatta (“non-self”) doesn’t entirely make sense. But at the least, know that Christian Eternalism-esque ideas of life after death are really not what Buddhist rebirth is about. “Awareness of Death”, or maranasatti - to be conscious that everything you are will end is considered by some teachers to be the single most important Buddhist practice.

5. Buddhist practice does not aim to suppress, dissociate, eliminate, or otherwise brain-damage emotional responses.

This misconception seems to be as common to people just starting meditation practice as it is to the general populace. There is a saying that to start Buddhist practice, “you have to be ready to quit suffering”. People seem to have endless justifications for why their suffering is essential, or is a deep and important part of the human experience. Or, they have the idea that if you do not go through enough pain, then you can’t have compassion for others, etc, etc. In short, everyone is identified with the wound.

Part and parcel with this idea is the misconception that advanced meditators and monks (who seek to end the suffering of themselves and others) are “numbing out” and suppressing all their emotions. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, beginning meditation tends to bring unprocessed traumas up, in much the same way therapy does, because meditation puts one more in touch with their body and feelings.

Dr. Tucker Peck discusses10 the way that psychotherapy is highly synergistic with Buddhist teaching. He poetically states that if psychotherapy is the work of “draining the swamp”, Buddhist practice is the process of learning to be ok with being knee-deep in muck all the time. If you’re going to dredge through all of your emotional issues, then it’s very helpful to be fundamentally accepting of them. The surprising part is that being ok with your stuff doesn’t reduce your motivation to clean it up.

A study of Theravada monks showed that when exposed to a painful shock (yes we have shocked monks for science), more advanced monks actually experience more pain than the average person.11 However, they have less aversive stress in anticipation, and they return to baseline much faster when the pain stops. They react less to pain which they have accepted. This is concordant with what every Buddhist teacher will tell you:

The type of equanimity we are developing is second-order. Enlightenment does not mean being happy all the time. It means being ok with feeling however you are feeling.

- Michael Taft

When our minds have fully accepted what is, we stop thrashing around and making things worse. An interviewer of the Dalai Lama recounted how the thing that was striking about the him was his fluidity. The Dalai Lama cried with a woman when she came in to tell him about her misfortune, and he was laughing with someone else 5 minutes later. Nothing is blocked and nothing sticks. Not repressed — fully present and sane.

6. Emptiness is not Nihilistic or uncaring, and it does not mean that nothing matters.

Related to 6, this misconception forms upon hearing Buddhists talk about “emptiness” (śūnyatā), “illusion” (māyā), or even “equanimity”. Buddhism does teach that everything arising in experience is “empty”, and has a “dreamlike quality”. Teaching using metaphors to shadows, The Matrix, and a video game are not uncommon.

The (understandable) misconception often sounds like:

But, if everything is an illusion, why care about anything at all? If everything is just a dream, aren’t I free to do whatever horrible thing I want?

The best answers to this I have heard are usually short and sweet: “But you DO care.” I think it is perhaps another scar of authoritarian Abrahamic religion, that people think we need to be made to care. If you are being honest, you do care, and adopting some heady Nihilistic justification won’t change that.

I sat in a classroom where Ken McLeod asked a student: “If your best friend tripped and fell while you were lucid dreaming, what would you do? You would help them, even though you knew it was a dream. Why? You just would.”

“Emptiness is compassion and compassion is emptiness.”

- The Prajñāpāramitā, considered the highest wisdom in Buddhism.

There is a beautiful and subtle optimism about human nature embedded in Buddhist morality. This optimism is that if we boil off all of the traumas, complexes, personalities, aversions, and reactions, we are nothing but love for one another, ourselves, and the world. It is natural to “hold space” for the struggles of others once we recognize the vast space pervading everything. So, we should practice kindness towards others and practice emptiness in view, each whenever possible — they lead to the same place.

People don’t need a reason to care. They need a reason to let their guard down. Let emptiness be that.

7. Faith is still important in Buddhism — it is just measured.

Buddhism, especially Western Buddhism and Theravada, often gets cast as a “rational” religion, devoid of faith. In contrast to the other religions of our culture, this makes sense. Whereas Christians centralize faith so much as to refer to their entire relationship with Christianity as “their faith”, you won’t hear Buddhists talking about faith as a virtue quite so often as “mindfulness” or “compassion”.

However, faith is still very important in Buddhism. It is faith that gives you the ability to move forwards despite not knowing (as we truly never do). Faith is what allows you to take refuge in the face of frightening mystery.

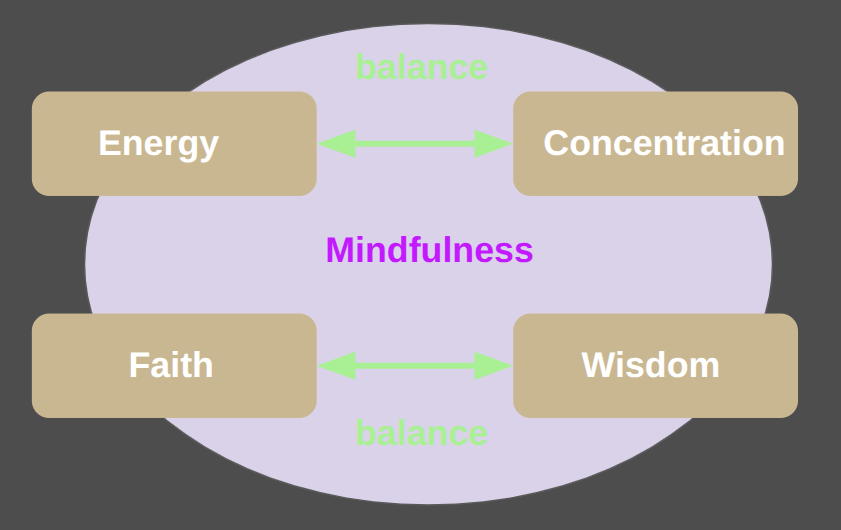

Buddhism casts faith as one of the “5 Spiritual Faculties”12. Four of these faculties, Energy, Concentration, Faith, and Wisdom, are described as being like the wheels of an ox-cart. Energy and Concentration must balance each other, just as Faith and Wisdom must balance each other. A cart with uneven wheels will run askew. These four qualities must be measured and balanced. Mindfulness is like the rider of the cart, actively balancing and steering it. It is said to be impossible to have too much mindfulness. But without the cart, mindfulness won’t go anywhere.

So, faith in what? There are many answers. The short answer (given by many teachers) is “whatever works”. A classic answer is “The 3 treasures”: Put faith13 in Buddha (the teacher), Dharma (the path), and Sangha (the spiritual family). Or, try any deity you have a relationship with. Avolokiteshvara is for everybody, not a bad place to start. Or, try your ancestors. Whatever works. But it is not at all faithless.

8. Buddhism does not claim to be the only true religion or path, but it also doesn’t think everybody is right.

I find Americans tend to think that religions are in one of two camps: either the Doctrine of Religious Exclusivity (“Thou shalt have no other Gods before me”/“There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his prophet”) OR some kind of free-wheeling “everybody is right” hippy-dom. People probably place Buddhism in the latter more than the former, but really, it’s in neither.

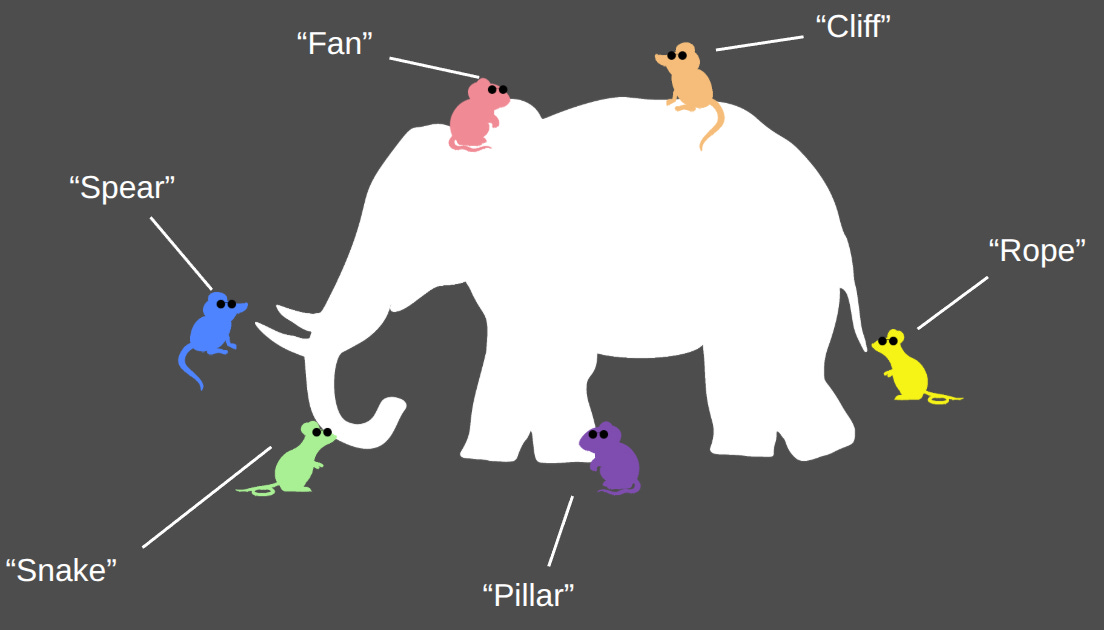

On, one hand, Buddhism is very much not a religion of the book: it started with spoken word14 and it lives in the unbroken chain of teacher-student transmission, not in the sutras. The Buddha lived to be 80, and had a very long pedagogical career, during which he explained things in various different ways. Seeing these different ways of teaching, it becomes clear that there is a truth underneath, which language can only approximate15. Think of the famous Buddhist story about blind men describing an elephant. Each perceives something different, because they don’t quite see the full picture:

This story displays that two very seemingly different expressions can be reflections of the same truth. The Buddha is also very clear on the fallibility of the Dharma, noting that the teachings will slowly erode and fade after a period of 5000 years. (we’re halfway in!) The Buddha even says that at some point along the path, you must let go of the path altogether, comparing it to a raft one uses to cross a river16. No textual infallibility or guarantees of absolute truth! There’s a reason you don’t see anything quite like the Christian or Islamic Fundamentalist movement in Buddhism17.

Buddhism is also open to other religions being correct. It has blended itself with Daoism to form Chan and then Zen, and Buddhism and Hinduism share many practices, beliefs, and deities. So, it is not exclusive.

BUT, this does not mean that Buddhism’s position is “everyone is right”, or anything of the sort. In fact, the very first sutta18 of the Dīgha Nikāya is a list of 64 different ways that a teaching can be wrong19! Buddhism formed during a time in what is now Northern India when there were many teachers (including atheists!), all preaching different dharmas. It was common for wandering ascetics and Brahmins to gather in town squares to compare, contrast, and debate elements of their dharmas. It is widely recognized that there were multiple ways to Brahma, and multiple paths to Enlightenment. But there are also false paths, and teachings that lead astray.

9. Enlightenment is a process, not a state.

An enormous amount of ink has been spilled on the topic of Enlightenment (or “Awakening”20). I think the default American view of Enlightenment, and my own past view, is that you “realize it” the same way that you realize a mathematical fact: insight hits (Eureka!), and then you have access to the fact forever.

However, for almost everyone, this does not seem to be how things work. This is too large a topic to cover well in a single section of an essay, but I’ll start with some basics. What is Enlightenment?

Enlightenment is a fundamental change to the way someone relates to and/or perceives reality.

An enormous amount of the Buddha’s teaching as well as modern Buddhist practice in every sect and tradition is oriented towards triggering this change deepening it.

Enlightenment alleviates suffering massively (but not completely!), for both the mind it occurs in, as well as those they interact with.

It has the character of a feeling of “realization” (whether this happens quickly or slowly). This realization recontextualizes all of experiences in a beneficial way. Consider how if you become lucid in a dream, it feels like a realization, and recontextualizes all of experience.

This way of perceiving is in some sense more “true” — the realization allows you to see things as they actually are. Consider how becoming lucid in a dream doesn’t eliminate the dreamworld. You have learned something additional about the way reality is21, and it is something that is apparent and true, and was true even before you realized it.

An integral part this mode of perception is the realization that “you” as you previously conceived/intuited/imagined, does not actually exist at all. This of course raises a lot of apparent paradoxes in the above points, which I will simply brush aside for this list, but they are important.22

So, what does this process look like? The short answer is different for different people, and different according to different traditions. There are, however, many models. One of my favorite models of the stages of Enlightenment is Roger Thisdell’s. Not because it’s universal, but because it is a practical example of the sort of thing we are talking about, and because he has great graphics:

This model makes it clear that the part of experience that feels like me can change steadily over time. For a deep-dive on different models of what Enlightenment is and how it progresses, check out Daniel Ingram’s compendium on this topic. One sort of model of Enlightenment that currently doesn’t exist is a biophysical/neuroscientific one. I am excited to make calls for such a model in a future piece.

Some people jump in the pond, and some walk slowly into the mist. Both get equally wet.

- Zen saying

But sometimes, the people who jumped in the pond go make a giant deal out of it, and then forget to ever jump in again.

- Michael Taft

10. Enlightenment is not Infallibility.

Talking about how Enlightened different people are feels a little taboo in the Buddhist communities I know. There are many good reasons for this, but one of them is because it plays into yet another American caricature of Buddhism: the image of an Enlightened master as someone who is perfectly wise or perfectly compassionate or good in all matters, both spiritual and mundane. Or, even worse, people might compare Enlightenment (or the related term “Buddhahood”) as a claim of divine authority.

But it is not so. I have heard it said that there are some asshole Arhats23. I have also met multiple people that I and others recognize as very Enlightened, and been astounded by how much presence, compassion, and wisdom these beings can project. But, they are still human. They can still be confused, imperfect, or unskillful. They can still have anger or sadness (though it does feel like there’s something unusually fluid and capacious about it when they do).

The Buddha teaches that there are 3 pillars of Buddhism: Morality (sīla), Concentration (samādhi), and Wisdom (paññā). Only the third pillar can be finished (if that), by complete Enlightenment. There is no being “done” with growing one’s morality, kindness, or competence. I believe that there are incredible Enlightened teachers walking the Earth, and it makes sense to both celebrate and learn from them while also knowing that they can forget their keys, say the wrong thing and hurt someone’s feelings, or stub their toe and curse.

Then I could maybe buy lunch in San Francisco.

Or, more precisely, many religions.

As opposed to Orthodox or Dogmatic.

Note this means being a Buddhist is non-exclusive with being a follower of various other religions.

This is not to say Buddhism has no concept of Justice. Check out some of the Tibetan warrior Dakinis. That’s just not what Karma is. Karma is broader, simpler, and less individualistic.

Buddhism rarely “mandates”. Morality in Buddhism is a practice taken out of compassion for the benefit of all beings. It is advice, for your own benefit. Remember this was a religion developed by homeless monks who refused to touch money for the first part of their history, not kings who imposed their holy doctrine on others.

Pew Research: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/06/29/religion-and-food/

Interestingly, the precept against alcohol (“sloth inducing drugs”) is much more specific.

This is super basic stuff, accepted by every single Buddhist sect. If the Buddhists had an equivalent of the Nicean creed that defines Buddhism, this would be in it.

Nicolardi, Valentina, Luca Simione, Domenico Scaringi, Peter Malinowski, Juliana Yordanova, Vasil Kolev, Federica Mauro, et al. 2024. “The Two Arrows of Pain: Mechanisms of Pain Related to Meditation and Mental States of Aversion and Identification.” Mindfulness 15 (4): 753–74.

https://www.mctb.org/mctb2/table-of-contents/part-i-the-fundamentals/6-the-five-spiritual-faculties/

Generally stated as “take refuge” or “seek sanctuary” in, but they are also used as a resourcing faith practice.

Pali had no script in the time of the Buddha. For the first few hundred years of the tradition, thousands of monks sustained knowledge by spending their lives memorizing and reciting it back and forth to one another.

Think Wittgenstein, or “The Dao that can be named is not the true Dao”

Alagaddupama Sutta, Majhima Nikaya 22

Not to say Buddhists have never gotten in religious wars. Far fewer than most world religions, but it’s happened.

Brahmajala Sutta, Dīgha Nikāya 1

In fact, one of these listed touches on the earlier point about rebirth: The Buddha states in this sutta that anyone who claims that a conscious or unconscious self survives after break-up of the body is incorrect.

Awakening is a colloquially broader term, but we’ll consider them to be the same thing for the purpose of this essay.

With all this talk of dreams, it is probably necessary to really hammer that this is a metaphor, if a good enough one to appear independently in religions around the world - from the Upanishadic to the Toltec. It is like realizing you are in a dream. Buddhism is not saying this is a dream. A dream is a dream, and the awake world is the awake world.

It is a matter of from which View we are speaking.

An “Arhat” is one who has attained the highest level of Enlightenment in traditional Buddhism and Jainism.