The Dendritic Nature of Being

You will never find yourself. But looking is one of the best things you can do.

Who is the real you?

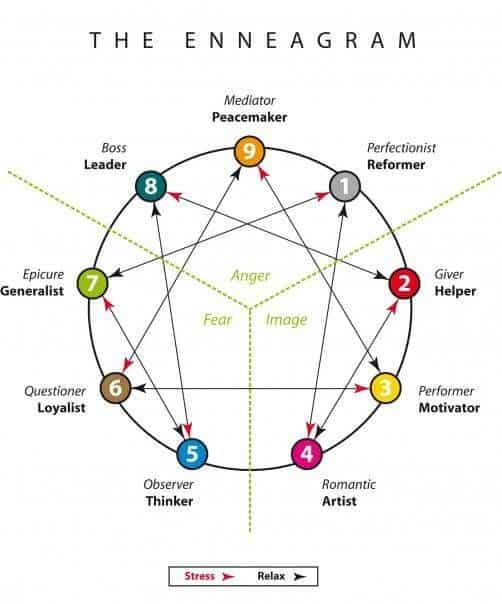

Since early high school, my friend Lilly Shi and I would spend hours talking about who we are. Lilly often felt like she was wearing different masks in different places, and felt the strain of resolving those different personalities - different selves. I didn’t quite feel the same strain, but all the same was fascinated by the question. We went through all the frameworks: MBTI, Enneagram, even Astrology (though being the odd non-Mormons in Utah will give you a distaste for the religiously-tinged). We’ve texted each other countless personality tests over the years. What’s our Harry Potter house blend? (Lilly would say Slytherin, but I suspect she’s got a small touch of the ‘Puff.) Lilly is a water-bender and I’m an air-bender. What’s our fantasy archtype? What color are each of us? We’d share, and nitpick, and compare each others’ experiences of ourselves and each other, over the course of almost two decades. We have watched each other grow and change too. Part of what makes the friendship special is that we’ve seen each other at various stages of life.

Perhaps it felt like if we found an answer, everything would suddenly be easy: “Got it! I’m an X type of person, and that means my job should be A, I should marry a B, and I should spend time on C! My faults are known and expected, and with the answers given, I can rest. I am a known quantity.” At some times, the activity itself seemed the point, rather than finding an answer. Stuff would come up along the way! An insecurity, a complex, a difficulty. Some feeling about parents, some core fear or guilt brought into the light. But regardless, the activity of self-inspection was undeniably juicy, a little bit weird, and seemed to endlessly yield beneficial perspectives and insights.

It is also notable that something about personality tests, frameworks, and psychology of self always feels a little bit flat. The more frameworks I read, the more I saw how none of them fit perfectly. Humans do not fall neatly within the lines that we draw for ourselves. An Enneagram that perfectly described us would be an Enneagram that had 9 billion types instead of 9. Similarly, the more I study mental health diagnoses and the DSM, the more I see they are falling prey to the same reductionism. These categories often aren’t describing something essential about the brain, they are a best attempt at describing the indescribable. Over time, I began to feel like there was no end to it. I described my true nature, to Lilly, as a “branching tree with masks for leaves” — dendritic, like the Greek déndron, meaning “tree”, after which the dendrites of a neuron are named:

Self-Inspection and Spirituality

Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time exploring various strains of spirituality, especially Buddhism (Theravada, Vajrayana). “Spirituality” is, of course, a bucket that is both vague and large. Does psychology count? Does philosophy count? But the more traditions I learn about, the more it is obvious that spirituality has a lot in common with the personality self-investigation that Lilly and I were into.

There are lots of big statements about what religion, spirituality, and mysticism are all about. Some philosophers (such as Kant) define religion circularly as being the answer to the question “what is God?” — a very Christian answer. Some people will define it as an investigation of truth, or an expression of love. Some people will define it as an embrace of the mystery of existence itself. For the purposes of this essay, I am going to claim that spirituality, religion, and especially mysticism, are doing something slightly more precise:

Spirituality is fundamentally an exploration of the relationships between the Self, the Other, and the World, and the path to deepening and integrating those relationships.

“Faith”, in this lens, is the trust that improving those relationships has the capacity to massively change your life and the lives of those around you in a positive way. Under this definition, psychology counts as spirituality. Therapy counts. Philosophy sometimes counts. Energy work counts. Probably Soul Cycle counts. Certainly a fascination with personality tests, “shadow work”, and emotional frameworks counts.

Some emotion-level shadow work with the excellent Heide Priebe

Branches Within

Internal Family Systems

This year, Robert Falconer, one founder of the popular IFS (Internal Family Systems) therapy, released “The Others Within Us”1. It is an incredible work of scholarship, clinical therapeutic practice, and cultural anthropology. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

IFS is a paradigm in which the nature of a singular internal self is challenged directly: we treat feelings, stances, or issues as parts in their own right2. There are “protectors”, “exiles”, and “managers”, and the paradigm offers a set of tools for working with each type of internal being. In IFS language, another critical element of being is capital-S “Self”: the true Self or “higher” Self. (which Falconer notes, can be compared to the Buddhist “non-self” that I discuss below, or the Sufi “beloved”) All evidence and clinical testimony show that the therapy is far more effective when our attitude is that these beings are as real as we are. This fundamentally relational approach to therapy is right in-line with a relational statement of spirituality.

But Falconer goes further than this. This this therapy is 20 years old, popular and effective, and cautiously accepted by our psychotherapeutic institutions…and Falconer essentially admits that it is exorcism and spirit work, of the sort that has been done all around the world for many years. In this book’s 300+ dense pages there are session transcripts, references to high-profile academic research, and interviews with spiritual practitioners of many types. They all point to the same reality: the human mind is alive with a vast multiplicity of beings.

Some beings may feel like “you” some may feel like “other”, and in many ways it makes no difference. Conversing with them directly, and granting them the same ontological reality you grant yourself is the most therapeutic, effective, and practical way to navigate the mind. Sometimes these parts dissolve back into the non-differentiated “trunk” of the inner tree of existence, and sometimes new ones spring forth.

Plurality

In our culture, we treat the idea of “beings inside the head”, or a multiplicity of beings, as a mental condition, or at the least abnormal. If someone has multiple distinct identified personalities, the DSM term is Dissociative Identity Disorder. In recent years, there has been work to spread awareness of people living as “plurals”, or multiple beings occupying one body.

For some period of years, I experienced a significant degree of inner multiplicity. The relationships were more or less healthy, so it did not cause me distress, as it might in someone diagnosed with DID. But there were inner conversations of various parts of the mind, in tightly cooperative and loving relation. It didn’t seem weird to me, because that was my reality. I assumed everyone had this experience to some degree, whether they noticed or not.

Incredibly, if you want that sort of experience it’s probably available to you with practice. An internet subculture exploded in recent years with a phenomenon called “Tulpas”—intentionally created, independently-acting, mental beings. The word and practice was pulled from Tibetan Buddhist esoterica, in which these mind-made beings can act as friends, daemons, archivists, and advisors. That this is even possible is fascinating on its own. (though it takes 100s of hours of practice) The Buddha says a form of multiplicity is immediately accessible from the 4th Jhana3, which, while in need to repeat experimentation, is true to my experience:

And so, with a mind thus concentrated, clear, sharp, bright, malleable, wieldy, and given to imperturbability…He then enjoys different powers: being one, he becomes many - being many, he becomes one…

- DN 2 (verse 87)

Finding the Center

The search for the “true self” can feel squirrely and strange. A shadow at the corner of your eye, that you can never quite place your finger on. I call being a tree, but one might as soon call it a matryoshka doll. Shrek called it an onion: peel back the layers, and there are new selves, new masks underneath. When they are all peeled away — no more onion. Lilly, the childhood friend whom I began this piece with, says she is an artichoke: the layers get weirder as you take them off — and sometimes they have spines.

Buddhism, Kenosis, and the Non-Self

So, when we look for ourselves deeper and deeper, what do we find? And as we look for ourselves, what happens? Theravada Buddhism frames the very core of the path to liberating enlightenment as the continual observation of 3 facts about phenomenal reality; the “Three Marks of Existence”. They are:

Anicca - impermanence. This translates well to English. Time isn’t real to experience. There is only now. Time is just a concept — a useful one, yes, but this human mind does not directly experience time. Everything passes. CS Lewis said “The present is the moment at which time touches Eternity.” Ram Dass said that all you really need to do is Be Here Now. My old roommate Xinyi told me that all unhappiness comes from either the past or the future. You regret the past. You’re ashamed of it. You compare it to what might be now. You fear the future. But things do not exist in time. They exist now or not at all. Without permanence, there is nothing lost but also nothing gained. Nothing regretted and nothing hoped for. It all passes. Dust in the wind.

Dukkha - Dukkha means suffering. We are all familiar with this idea. It’s like the hamster wheel of the hedonic treadmill. You desire things. Desire exists to push you in a direction, it doesn’t exist to be fulfilled. As soon as you get what you want, you want something else. As a mark of existence, it can be read as Nothing you will ever experience is ultimately satisfactory. While Buddhism teaches that “a being cannot exist in Samsara (the formed world) without suffering”, it also teaches that the amount that one suffers can be massively reduced through practice. Some modern practitioners claim that 90-99% of the average person’s suffering is the result of unnecessary delusion. Even physical pain can be greatly transformed, to be still-informative but not so laden with torment.

Anatta - the “non-self”. This mark of existence is the weirdest, perhaps the most liberating, and the most pertinent to this essay. It is, put simply: Nothing you have ever experienced or ever will experience is “you”. Does that mean you don’t exist? Sort of, but not quite. You don’t not exist either. There is not 1, not 0, and not many selves. Weird, right? Existence is. But the feeling of “self” is a sort of confusion we developed at some point. We intuitively think we need it. It feels like survival. But it isn’t, and at the end of the day, the confusion is only hurting us. The psychedelic phenomenon known as “ego death” is probably a temporary unsustainable somatic realization of this fact.

These three characteristics were centuries later summarized as shunyata, or emptiness. As (“The Arahant”) Daniel Ingram puts it4: “know that things come and go, they don’t satisfy, and they ain’t you. That is the truth. It is just that simple…it is rightly said that to deeply understand any two of the characteristics simultaneously is to understand the third, and this understanding is enough to cause immediate first awakening.” Dharma teacher Michael Taft teaches that one should continually observe this “emptiness” of the self. To search, again and again, for the self at the center of experience, and not find it. This is what will transform your experience like nothing else.

This Buddhist approach to enlightenment is what the Christian mystics refer to as “Kenosis” - the way of emptying the self5, to contrast it with “Theosis” - the way of reaching out to God. (which is similar to some Sufi and Hindu teachings) Paradoxically, incredibly, these two approaches lead to the same result.

Subhuti, no one can be called a bodhisattva who creates the perception of a self or who creates the perception of a being, a life, or a soul.

Branching Outwards

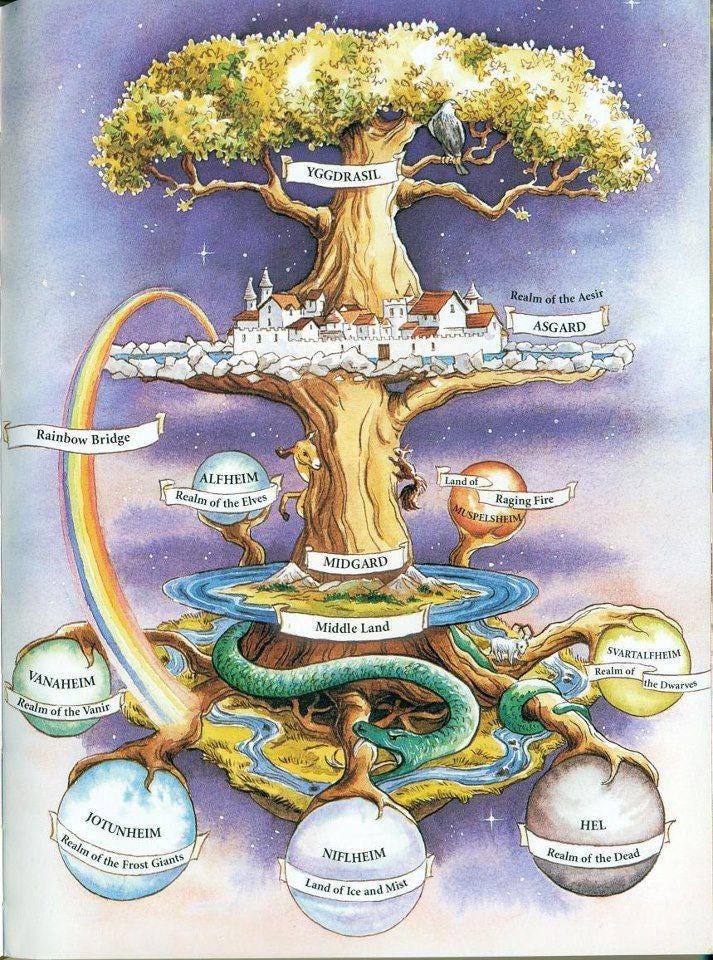

We’ve been talking about inwards, but what about outwards? There is a recursive and branching there as well. Just as there is a human body composed of sensations, there is a family composed of human bodies. A community composed of families, and movements and cultures composed of communities. The Norse described all the realms of existence as existing on the massive tree Yggdrasil. This may be a metaphor (or rather, a phenomenological reality) for the realms of direct mystical experience.

So if we go back to basics, and observe our felt experience of the world outside of us, what can we find?

There is a world. (Wittgenstein starts here.6) We don’t particularly have to know exactly what it is. But it’s big. Too big for you to comprehend, and too big for you to describe, except using silly abstractions. (ineffable) Even if you do try to describe it in words, it’s not the same as experiencing it.

That world is alive. Just as the world is bigger than you, it is also smarter than you. It contains human beings like you. It also contains ecosystems, corporations, cultures, AIs, dolphins, complex laws of nature, and perhaps trillions of aliens. But there’s something else beneath this technical statement. The world feels alive, in the same way you are. Pause. Look.

You have a relationship to this world. And that relationship uses some of the same relational instincts that you use in your standard human relationships. You can address the world. At some level, whether you admit it consciously or not, you feel a certain way about the world. It’s kind. It’s a dick. It betrayed you. It followed through on its promise. Life is a bitch…she’ll knock you around and she’ll lend you a hand. You can’t eliminate this narrative by deciding it doesn’t make sense, and even if you could, it wouldn’t necessarily serve you or help you navigate the world better. Your living, personal, relationship with the world is, in materialistic terms, a fact about your psychology.

You are not separate from the world. I could cite physics, or traditions, or philosophy here. But instead, I challenge you. Find the boundary. In your own experience, feel/look/touch/taste/sense the exact point where you stop, and everything else starts. The place where experience has some uncrossable wall separating you from everything else.

Collective Being

Mystical Traditions do not only speak of beings as being contained strictly to one body or mind. Buddhist cosmology, and practically every cosmology except modern scientific materialism, is rife with devas, asuras, spirits, angels, demons, nymphs, dryads, ghandarvas, ghosts, and all manner of beings that, while bodiless, nevertheless exist and have actions which affect the world. They inhabit, to some degree, the shared inter-subjective reality of many.

The Devas too, are Dendritic

If you read about devas (Hindu or Buddhist gods), you will quickly learn that their individuality is similarly not so set in stone. There are many different aspects of Tara, that are all the goddess Tara but different beings from each other. Avolokiteshvara is Guanyin, but one is male and one is female.

Egregores

1800s occult language gives us the fantastic term of egregore. An egregore is a being arising from the collective conscious. In modern terms, it’s not entirely unlike a memeplex. A great example is Santa Claus. Does Santa Claus exist? Sure, Santa doesn’t have a material canonical human body. Yet…the claim is that Santa Claus gives presents to children on Christmas. Because this story is told and spread among parents, children are, in fact, given presents on Christmas. The spirit of Santa is a Clausal mechanism! We cannot say that Santa is even dead, or non-intelligent, as Santa Claus’s story and actions are implemented on the minds of intelligent living humans.

Sure, we could say Bob is just pretending to be mall Santa. But might it, in a sense, be equally accurate to say that the spirit of Santa has possessed Bob’s body, while he is dressed up and acting like Santa? It was arguably a voluntary possession. But Bob is embodying Santa’s agenda, spreading cheer to children at the mall. It looks like Santa, it acts like Santa, it does what Santa set out to do…it’s pretty fair to say it’s Santa!

Christianity Too

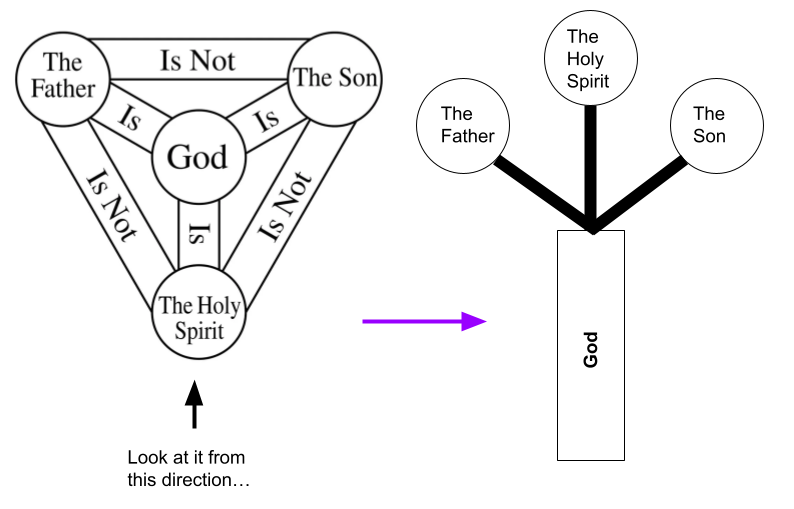

Christianity also plays with the identity of being. Take the “shield of trinity”, a diagram which shows the relationship between various Christian aspects of God (they get mad if you say gods with a plural), and turn it sideways:

It seems that this same kind of “is it one?”, “is it many?” fuzziness can apply to the gods/devas/spirits/critters, just as it does to our own sense of being. It is a continuum of branching being.

The Dendritic Nature of Brain

Ok, let’s come back to materialist Earth for a moment. All of that sounds, to our culture’s ears, crazy. People spawning other people in their heads? People as the pieces of vast beings formed of mind, myth, and meme? And yet, I can’t help but notice that from everything we know about the brain, it is eminently reasonable. The human brain is massively plastic, parallel, and asynchronous, and it is full of holistic fractal structure. We tend to think of our “selves” as some kind of captain, sitting in the command seat, making the high-level decisions, that are translated to lower, but if that’s the case…why can’t we find the command center7 in neuroimaging studies? The body has to take coordinated action, and we have to present a social interface to others. But there is a lot of wiggle room there for all manner of internal experiences8.

As a computational neuroscientist, I often make such analogies between brains and computers9. The analogy that many people first conceive of looks something like: input, decision, action, output. Step by step. But the brain looks much less like a CPU doing one thing after another, and much more like a GPU — and in fact far more asynchronous. A continuous splitting and rejoining of gossamer activity. After a meditation retreat I wrote the following, programmer-geeky contemplation:

Am I a thread?

If this fork rejoins, would anything notice?

Anatta means not 1, not 0, and not Many.

But is Many any further from truth than 1?

There is simply no reason that the architecture or environment of the human brain needs there to be one solid, canonical self, without permeable boundaries. In some way, Occam’s Razor is exactly what every spiritual tradition has been telling us: We are, altogether, many and none and one. An ocean of vibrating being, our individual divided selves nothing more than an eddy in the current. Bodies, thoughts, energy, movements.

So no, you will never find yourself — not like you were thinking when you set out. But the fierce examination of the twisting branches of being within, above, around, and in every direction is the noblest of searches. I could end on a more sober note, but the careful scientist is but only a single mask of this mind, and I think I’d rather leave you with an excerpt from Touch Fucking Moonflower’s, A Provisional Manual of West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druidry10:

It’s impossible to say. There is in fact no single moment at which we learnt this thing. Maybe we knew it when we were born and forgot it for a while, maybe we knew it before we were born and needed reminding; maybe every event in our lives, every boulder, every flower, every friend and every enemy, was conspiring Somehow to remind us.

To remind us that Everything is Made of Everything Else.

…and our whole practice is to deepen and celebrate this understanding.

Falconer, R. (2023). The Others Within Us: Internal Family Systems, Porous Mind, and Spirit Possession. United States: Great Mystery Press.

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model. United States: Sounds True.

The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya. (2005). United States: Wisdom Publications.

Ingram, D. (2018). Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha: An Unusually Hardcore Dharma Book - Revised and Expanded Edition. United Kingdom: Aeon Books Limited.

Red Pine Translation (2009). The Diamond Sutra. United Kingdom: Counterpoint. (original text - circa 200 BC)

Wittgenstein, L. (2022). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Chiron Academic Press - The Original Authoritative Edition). Sweden: Wisehouse.

Damasio, A. R. (1999). The Feeling of what Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. United Kingdom: Harcourt Brace.

It is almost certainly the case that cultural conditioning plays a role here as well. If the social interface trained into you requires you to think “I am one entity living in this body”, your experience might reflect that. If it’s socially acceptable for spirits to be coming and going, your experience may reflect that too.

Even though Konrad Kording says we shouldn’t.

Jonas, Eric, and Konrad Paul Kording. 2017. “Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor?” PLoS Computational Biology 13 (1): e1005268.

Touch Fucking Moonflower and the People of the Great Assembly. (2024) A Provisional Manual of West Coast Tantrik Psychedelic Druidry. Independently Published