Wedding Ritual Design for a Pluralistic Society

A recollection of, and guide to, hand-crafting a syncretic, modern, and personal wedding ceremony.

This Isn’t Normal

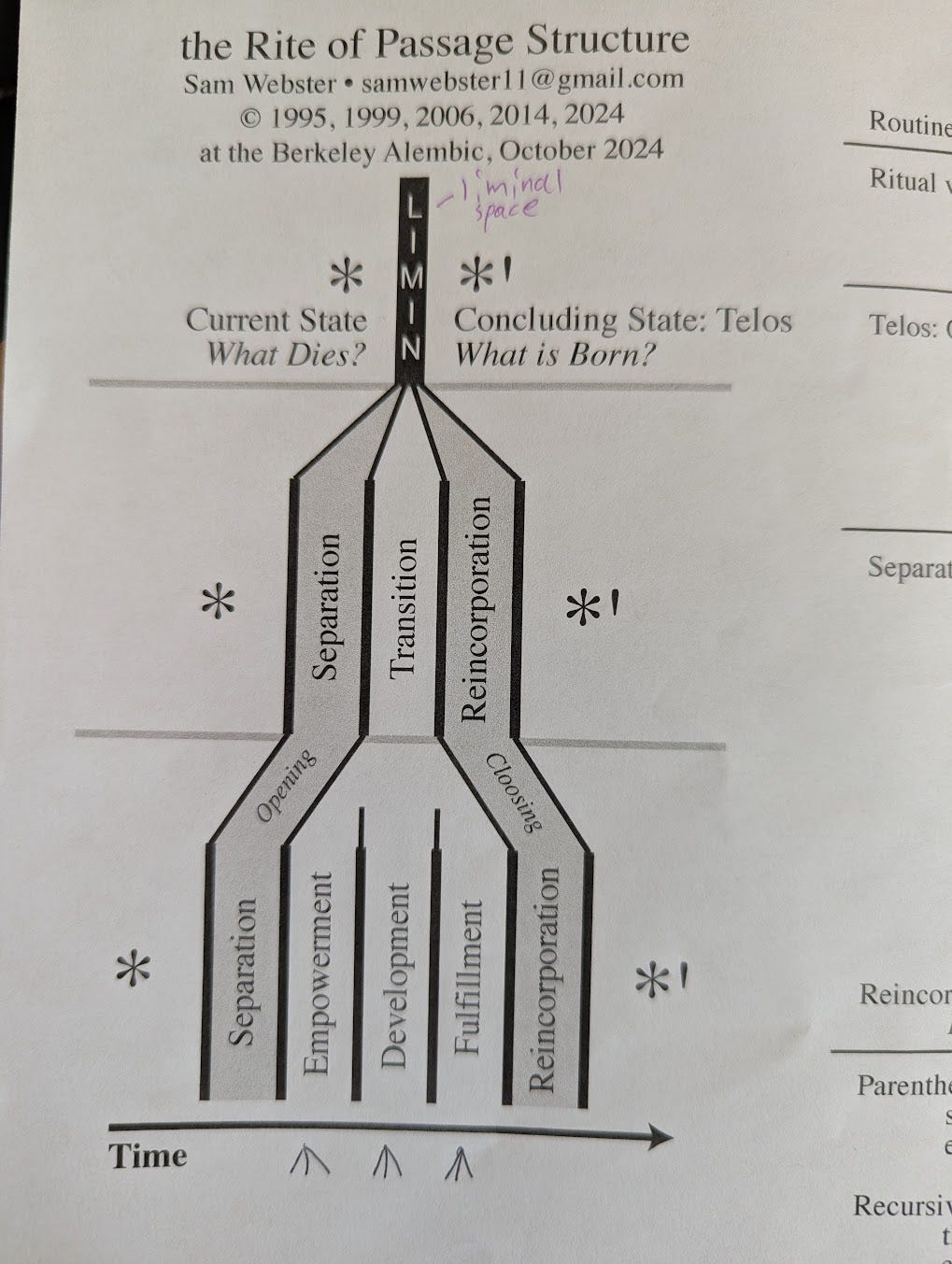

"We are the only major culture without a strong ritual tradition”. These were the words with which Sam Webster (M. Div, PhD, Mage) chose to open his class on Transformative Ritual Design. Sam is both an academic expert on ritual tradition around the world, and an experienced practitioner with ordainments in multiple traditions, Christian, Buddhist, and Thelemic. I highly recommend taking anything he teaches. However, several points, especially from his first class, feel extremely poignant in giving perspective to the situation our society is in:

Ritual use stretches back into the reaches of prehistory, and may be coincident with sapience itself.

Ritual serves a purpose as a tool for self and communal transformation. The boys need to become men, the dead need to depart, and the lovers need to become a family.

In much of the Western world, we are experiencing the aftershock of Catholicism’s incremental extermination and replacement of local ritual traditions. (Islam did this too, but elsewhere) This was followed by hundreds of years of, to put inquisitions and the protestant reformation shortly, drama, where Catholicism ultimately failed to replace the spiritual technology1 it had destroyed. Much was lost.

It is not that we are completely without ritual. A handshake is a ritual. A birthday party is a ritual. But some amount of our high rates of mental illness, and the problems of atomic modernity, can be attributed to us losing this important tool. If we want to move forwards, we are going to have to revitalize them.

Just before taking Sam’s class, I had had some hands-on experience with this challenge, as I officiated the wedding of my friends Jake and Kerry. (I had the luck to be able to consult with Sam and others beforehand about it though.) What follows is a record of that exploration, some philosophy behind it, and tips to you if you ever find yourself in a similar role, whether as an officiant, or some other master of ceremonies.

So, you’ve been asked to officiate a wedding…

This was my third time being asked to officiate a wedding for friends, but never had I been given such a blank slate. The first wedding I officiated was low-key event in the Detroit auto museum, where the couple’s own vows filled a lot of the content time, and I mostly just had to tell stories and make jokes. The second was held in Beijing, and wedding planners had already prepared an expansive set of rituals from various dynasties to enact. For that wedding, my role felt more like “MC”: intro-ing the English-speaking guests to the different parts of the ceremony, while my Mandarin-speaking counterpart Li did the same for Chinese attendees. This third ceremony was clearly going to be a bit more prep.

My friends Kerry and Jake are nice in that Canadian brand of wholesome, both very intelligent Chemists, and apparently trusting enough to say “just get up there and be yourself for half an hour. I’m sure it will be great!”, when asking me to be their officiant. Their easy-going and optimistic nature is a wonderful quality to be around as friends, and I’m sure it will serve them well in their marriage, but it didn’t exactly give me a framework to work on. In addition, this wedding was a bigger affair than the previous two, with much of Jake’s enormous family, and many childhood friends attending the beautiful Pennsylvania venue. Jake, Kerry, and I are all professional researchers, and it was obvious to me that I would have to do some research, of both tradition and of the couple.

Doing your Homework

Telling the Story of The Lovers

In my experience, one of the first jobs of a wedding officiant is to tell the story of the bride and groom’s romance to the crowd. Many of the people attending will know one of the two, but not both. In addition, even if some friends and family know both of the two, it can be hard to see the internals of a relationship from the outside. A wedding is as much (probably more!) about the couple’s family and community as it is about the couple themselves. If everyone does their job perfectly, the guests will all leave the wedding feeling sympathetic joy, support, and approval for the relationship. And they cannot approve what they do not know. Of course, a story is just a story; it cannot capture the full complexity of a human partnership. But a good story will have a large helping of truth, and be delightful besides.

Giving an Interview

As an officiant, the interview is crucial. You cannot tell a good story without some material to work with. In addition, as a couple busies themselves with wedding preparations and the stresses of daily life, it’s good to help them reflect on the relationship itself, and remind them of why they are doing what they are doing. A wedding is a ritual, and the most powerful rituals are ones backed by the strongest of intention. If the intention of the you and the couple are both loving and clear, it can’t help but go well. I asked Kerry and Jake many questions. One thing I did differently from past officiations is that I gave them each a 30-60 minute 1:1 interview in addition to talking to them together. Couples about to marry tend to be pretty attuned to one another, and I feel like it’s good to see a bit of each individual, without the influence of the other in the room. I also made sure that not all of my questions were softballs. You want both the good and the bad on the table. Here are some examples:

What is one thing you admire about your fiance?

What is one way that they make your life easier?

What was your first fight?

What was your first impression of them?

What is something you can do that always cheers them up?

If you were a team of fantasy adventurers what would you be? (ok, this one might be a little customized to Kerry and Jake)

What is annoying about your fiance?

If you are exhausted, why is going home to your fiance good?

What is something about your bachelor(ette) life that you feel like you might miss? It can be big or small and silly, specific or vague. (This one will be important later!)

Of course not everything will go into the ceremony. You’re getting a picture of the couple here, as well as mining for content and jokes. You want to get a picture of not just why the couple likes each other, but how they balance each other. Do they take particular roles? Are they opposites attracting, or birds of a feather flocking together? Take all answers, whether silly or serious, and ask many questions, both spicy and sappy.

There are also practical questions concerning the preferences of the couple in your storytelling. Consider:

Should you hint about future kids in the ceremony? Parents love it, but the couple might not!

Exactly how much detail do you include in your storytelling? Friends might enjoy hearing about drug-fueled burning man adventures, but you don’t want to give grandparents heart attacks!

How religious should it be? This might be obvious, but it might not be! Religious references should be a combination of what will please the couple, what will please their audience, and what you as an officiant can provide with integrity.

Reading Prior Art

People need ritual. We are creatures of tradition. Yet, we do not live in a traditional time, and the US is not a traditional country. We live in a syncretic, pluralistic, society, and almost everyone who lives here, whether they realize it or not, is to some degree multicultural. Our tendencies, the words we use, the food we eat, and the memes we share are the product of a global exchange of ideas. There really no such thing as a “traditional American wedding”, the same way that traditional (pre-Colombian) Chinese food is not actually spicy, and French Fries are not actually French. We have entered, and are quickly accelerating into, the age of global endlessly recombinating cultural soup. Whether the couple’s ancestors are recent immigrants to this country, have been here a while, or native — if you ask your couple to rattle off their familial heritages and religious or anti-religious influences, you’ll likely get a large list, if they know it at all. How do we root a couple to their past, to the earth, and to tradition in an age such as this? How do we help them find their place in the endless story?

I read as many wedding rituals around the world as I possibly could. Armenians balance bread on their shoulders to ward off evil, and eat spoons of honey to symbolize happiness. In Xinjiang, the groom shoots the bride three times with headless arrows, then collects them and snaps them in half. In Germany, guests break plates, and the couple cleans them. In Spain, they chop up the tie of the groom and sell the pieces, and in Cuba there is the “money dance” - where every man at the party has a chance to dance with the bride, and pins money to her dress if he does so. Around the world, there is breaking of glasses, sticks, and dishes, tying of knots, eating of symbolic foods, and many games and challenges, usually given to the groom. There is the reading of holy books, the reciting of mantras and prayers, the eating of special foods, and the wearing of special clothes. Every choice can be a symbol, whether subtle or announced.

Consulting with Experts

In a truly auspicious manner, I had the luck to stumble into Sam, my local wizard at the Sangha. I asked both Sam and Michael Taft, my local Dharma teacher, their advice on creating a ritual. Over the course of a conversation with each of them, and some poetic coining by the ever-brilliant Elise Liu, a framework took shape.

What Makes a Wedding Ritual?

I believe that a wedding ritual, or at least a wedding ritual worth its salt, is composed of three primary elements, which we shall call Breaking, Binding, and Blessing. (And Sam notes that any ritual is about the breaking of old bonds and the formation of new ones.)

Breaking

Whether it is the aforementioned Spanish cutting of the groom’s tie, or whether it is the ancient roman practice of burning the axle of the wagon in which the bride arrived, all marriages rituals need to acknowledge what is ending. It could mean the end of life as bachelor or bachelorette, or it could mean finally letting go of previous romances, but either way, it must be said: to be wed, like any real choice in this life, is also to give something up, and while we may give it up gladly, we should not pretend that we aren’t. Breaking rituals symbolize that what is happening here, cannot be reversed. It is an act of entropy. Just as a ritual glass or plate may be broken, the couple will each be letting go of aspects of your old lives. Whether the new couple’s life together is short, or as everyone wishes, long and happy, they will not be able to return to what life was before, any more than scattered shards of glass can be reassembled.

The traditional line “If there is anyone who has any reason that this couple should not be wed, speak now or forever hold your peace” I consider to be a breaking element, and a good one to include. The opportunity to cause some drama and change hearts and minds has passed. Let it go. (It is also an excellent moment of dramatic tension.)

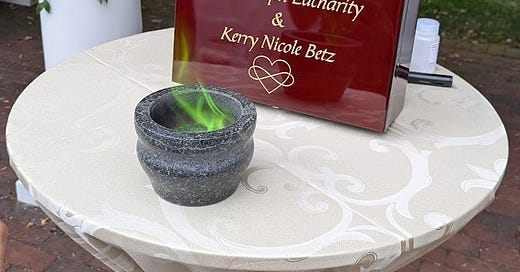

For Kerry and Jake, I riffed on their professions as chemists. There would be no plates, but reagents, crucible, and combustion. To Kerry I handed ceremonial (but very real, synthesized in my garage!) orthoboric acid, and to Jake I handed some Methanol. I told them that the boric acid represented Kerry’s colorful and creative nature, and the Methanol was the warm and consistent fuel Jake brings. We lit it up, and let it burn for a moment, a bright green to match the bridesmaid’s dresses and groomsmen’s ties.

Then came more letting go. I went back to the interview question I asked them each, about what they missed about single life, and gave them tokens representing that (which I shall not include here). I asked them to each toss their tokens into the flames - and to give the moment watching the burn to themselves, individually. The couple will not cease to exist as individuals, but it will be different.

Binding

Like, wedding rings themselves, all wedding rituals must symbolize and provide a threshold, for entry into partnership. Both Sam and Michael urged me to tell the couple: even if they have lived together for years, marriage is not perfunctory. Something will feel different. There are many ways to represent binding, and most of the traditional ones are pretty on the nose: ropes and ties. Vows as well, are a binding ritual.

Even if they have lived together for years, marriage is not perfunctory. Something will feel different.

Kerry and Jake are both avid climbers, and on the wall with their lives in each others’ hands several times a week. As such, I presented them with a ritualistic (i.e. real, but short) climbing rope, and asked them to tie each others’ wrists using a standard figure 8. I told them that there will be times in each others’ life when they have to switch back and forth between being the belayer and the climber, but that regardless of who’s climbing at the moment, they are both connected on one adventure.

It was at this point in the ceremony that they also exchanged rings and vows, and we signed the marriage contract. A triple-bond of rope, vow, and law.

Blessing

The final component in this framework is Blessing. Cultures around the world, give the couple gifts, shower them with rice, and ask that the universe protects them in this new chapter of their life. This is where more religious components will live. The goal of blessing is to anchor the couple not just to each other, but the world around them. Like the previous two, what exactly is done here will depend on the couple. I highly encourage audience participation for this component. It is as much about the community’s blessing of the couple as about their relationship with some higher power.

For Kerry and Jake, we kept it light and vague, like the religion of most of their guests. I invited at the moment I pronounced them husband and wife, for everyone to raise their hands in the air to shout an exclamation of their choice. It could be Amen! Hallelujah! the Buddhist Svaha!, or a simple Heck yea!. We snapped a picture to go in the couple’s nuptial artifact box, and let the party begin.

Closing Thoughts

Overall, I love officiating, and would be happy to do it again. Perhaps I’ll someday broaden it to beyond my personal friends. I’m a sucker for romance, I love storytelling and public speaking, and there’s even a bit of magic. It’s a benevolent creativity of the sort I love most. I hope that if any of you ever get such an opportunity this experience and framework will help you along your way!

It can be hard, without the weight of a clear cultural identity and context, to make a wedding fun, magical, and personal, and yet not feel arbitrary or lack gravitas. We are in a new context, and I see tradition as something which we can neither ignore nor take for granted. It is something we are constantly co-creating, weaving out of the many threads of the past. And we need to lay good foundations, for ourselves, and for those who come after us.

“Spiritual Technology” sounds like some silicon valley neologism, but it really isn’t. “Tantra”, the movement that overtook both Buddhism and Hinduism around the 5th century can be accurately translated as “technology” — and that is what it is: tools to assist in direct spiritual practice.

This was beautiful, Carson - very thoughtful and appropriate. Thank you so much for officiating for Kerry and Jake, and for being such a good friend to them. Sveiks!